When the Somerset Levels flood in winter, their reed-lined waterways spread into a shimmering inland sea – haunting, half-remembered.

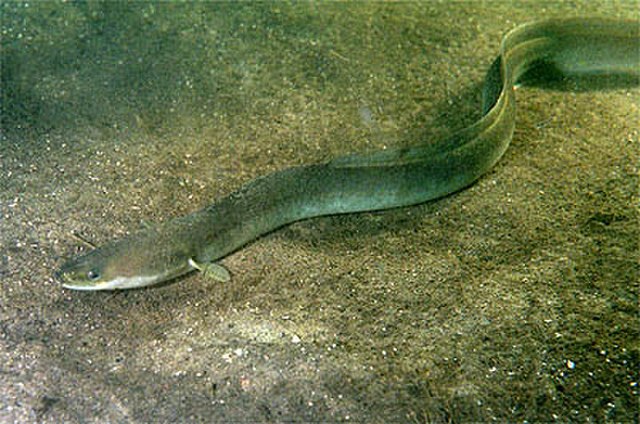

Generations ago, these wetlands throbbed with the seasonal arrival of eels: twisting through rhynes – man-made channels – and ditches in their thousands, netted in baskets, celebrated in song, even paid as rent to Glastonbury Abbey. Today the waters move more sluggishly and sparsely, their once-teeming channels reduced to faint traces of what was.

Determined to reverse this decline, the Somerset Eel Recovery Project is stitching together science, folklore and community creativity to restore not only the eel but a lost sense of place.

Its mission is both ecological and cultural: to rescue a critically endangered species while reviving the stories, songs and traditions that once made Somerset an eel country.

Vanessa Becker-Hughes, one of the founders, has forged partnerships across science, policy and the arts. She leads a fast-growing schools programme – last year, 60 eel tanks were set up in classrooms – alongside storytelling events, traditional rope-making workshops and citizen science projects that test for eel DNA in rivers.

“I try to come at it from different angles,” she said. “Sometimes we do science, sometimes we do a river blessing. But it’s all about connection.”

The initiative has attracted high-profile champions. Feargal Sharkey, the former Undertones singer turned clean water campaigner, has amplified the project online, calling it “a vital act of ecological and cultural restoration”. Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall, the chef and sustainability advocate, has been named an official “eel legend” – a playful title for fundraisers who support habitat restoration and education.

“Eels have fascinated me for a long time,” he said. “I have gone from poacher to gamekeeper: cooking them to realising how important it is to protect these extraordinary, charismatic creatures. They are a keystone species with a remarkable natural history, that deserves our respect and our custodianship.”

Across Europe, the population of the European eel has fallen by more than 90% since the 1970s. In Somerset’s Bridgwater Bay, once a thriving entry point for glass eels, numbers collapsed by 99% between 1980 and 2009.

The causes are complex and interlinked: overfishing, pollution, migration blocked by infrastructure, climate change and a parasitic nematode that damages the eels’ swim bladders.

Becker-Hughes’ mix of wonder and urgency drives her mission. She believes that rekindling our relationship with eels requires rekindling communal memory – through rituals, craft and shared experience.

“We make straw ropes, which we put over barriers. They get wet and the little glass eels use them to climb up and over. But more than that – it gets people to visit these weirs. They notice the water. They count the eels. They start to care,” she said.

Andrew Kerr, chair of the Sustainable Eel Group, notes that eels once shaped placenames, livelihoods and local customs. Restoring that bond, he argues, is essential.

“If we lose the eel, we lose a sense of our identity. We forget the songs. We forget what this landscape was,” he said.

Becker-Hughes said all is not yet lost. “Each spring tide still brings new arrivals,” she said. “The eel is not just a ghost of the past – it is a key to unlocking something vital in the present.”

With every story told, every rope woven, every child watching a glass eel wriggle up a straw ladder, Becker-Hughes believes a fragment of species, memory and care is restored.

——————————————————————————

At Natural World Fund, we are passionate about restoring habitats in the UK to halt the decline in our wildlife.