Human activity has brought the world dangerously close to the brink of multiple planetary crises, with only one out of eight indicators of planetary safety and justice remaining unaffected, according to a groundbreaking analysis of global well-being.

The report, conducted by the Earth Commission group of scientists, goes beyond the well-known issue of climate change and sheds light on other pressing challenges such as water scarcity, nutrient overload, ecosystem degradation, and aerosol pollution. These issues not only pose threats to the stability of life-support systems but also exacerbate social inequalities.

Published in the prestigious journal Nature, this study represents the most ambitious effort thus far to merge indicators of planetary health with those of human welfare.

Prof Johan Rockström, one of the lead authors, said: “It is an attempt to do an interdisciplinary science assessment of the entire people-planet system, which is something we must do given the risks we face.

“We have reached what I call a saturation point where we hit the ceiling of the biophysical capacity of the Earth system to remain in its stable state. We are approaching tipping points, we are seeing more and more permanent damage of life-support systems at the global scale.”

The Earth Commission, established by numerous leading research institutions worldwide, aims for this analysis to serve as the scientific foundation for the next generation of sustainability goals and practices. It advocates for a broader scope that encompasses not only climate-related targets but also other environmental indices and considerations of justice. The hope is that cities and businesses will adopt these targets to measure the impact of their activities and work towards a more sustainable future.

The study introduces a set of “safe and just” benchmarks for the planet, drawing an analogy to vital signs for the human body. Instead of examining pulse, temperature, and blood pressure, the researchers analyse indicators such as water flow, phosphorus usage, and land conversion. These boundaries are based on a synthesis of previous studies conducted by universities and UN science groups, including the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services.

The findings reveal a grave situation in almost every category. While setting global benchmarks proves challenging, the world has already committed to keeping global heating as low as possible, with a target range of 1.5 to 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. However, the Earth Commission argues that even this range is perilous, given the severe impacts of extreme heatwaves, droughts, and floods currently experienced at a temperature increase of only 1.2 degrees Celsius. They propose a safer and just climate target of 1 degree Celsius, which would necessitate significant efforts to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Moreover, they emphasise that stabilising the climate is impossible without protecting ecosystems.

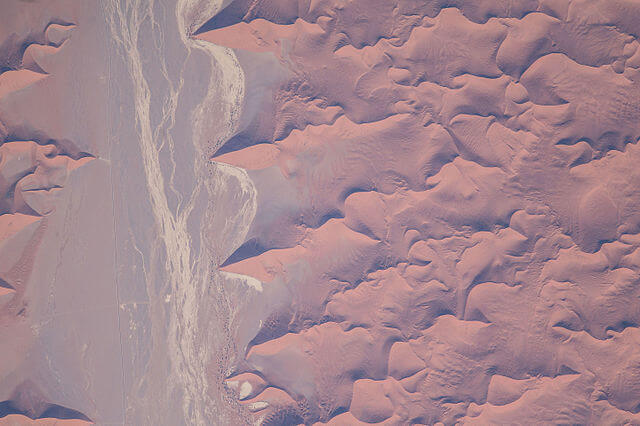

To achieve this, the Earth Commission recommends that 50 to 60% of the world should consist of predominantly natural ecosystems. However, the reality is that only 45 to 50% of the planet still maintains intact ecosystems. In human-altered areas like farms, cities, and industrial parks, the commission argues that at least 20 to 25% of the land should be dedicated to semi-natural habitats such as parks, gardens, and tree clusters to preserve essential ecosystem services such as pollination, water quality regulation, pest and disease control, as well as the mental and physical health benefits associated with access to nature. Sadly, two-thirds of altered landscapes fail to meet this goal.

Aerosol pollution is another critical target for improvement. The report highlights the need to minimise the disparity in aerosol concentrations between the northern and southern hemispheres, as this disparity can disrupt weather patterns and monsoon seasons. At a local level, such as in cities, the study follows the World Health Organisation’s guideline of a mean annual exposure to PM2.5 (small particulate matter) not exceeding 15 micrograms per cubic meter. This boundary is crucial from a social justice standpoint, as marginalised communities, often predominantly Black, tend to suffer the most severe consequences due to their vulnerable locations.

In terms of surface water, the report establishes a benchmark that no more than 20% of river and stream flow should be impeded within any catchment area. When this threshold is exceeded, water quality declines, and freshwater species lose their habitats. Unfortunately, hydroelectric dams, drainage systems, and construction projects have already surpassed this “safe boundary” on one-third of the world’s land. Groundwater systems face a similar predicament, where the safe boundary dictates that aquifers should not be depleted faster than they can replenish themselves. However, alarming rates of depletion occur in 47% of the world’s river basins. This issue is particularly severe in densely populated areas like Mexico City and regions with intensive agricultural practices, such as the North China Plain.

Nutrient management also emerges as a significant concern. Wealthier nations tend to use excessive amounts of nitrogen and phosphorus in agriculture, resulting in runoffs that contaminate water systems and trigger harmful algal blooms, rendering the water unsafe for human consumption. The report emphasises the importance of global equity in this domain, suggesting that poorer nations require more fertilisers, while wealthier nations must reduce their surplus. Achieving a balanced approach would mean a global surplus of 61 million tonnes of nitrogen and approximately 6 million tonnes of phosphorus.

The authors of the report stress that while the planetary diagnosis is grim, there is still hope for recovery, albeit with limited time remaining.

Joyeeta Gupta, the Earth Commission co-chair and professor of environment and development in the global south at the University of Amsterdam, said: “Our doctor would say the Earth is really quite sick right now in many areas. And this is affecting the people living on Earth. We must not just address symptoms, but also the causes.”

David Obura, a member of the Earth Commission and director of coastal oceans research and development in the Indian Ocean, acknowledges that the policy framework necessary to restore balance within safe boundaries already exists through existing UN climate and biodiversity agreements. However, he emphasises that individual consumption choices must also play a crucial role in driving change and ensuring a sustainable future.

“There are a number of medicines we can take, but we also need lifestyle changes – less meat, more water, and a more balanced diet,” he said. “It is possible to do it. Nature’s regenerative powers are robust … but we need a lot more commitment.”

——————————————————————————

At Natural World Fund, we are passionate about stopping the decline in our wildlife.

The declines in our wildlife is shocking and frightening. Without much more support, many of the animals we know and love will continue in their declines towards extinction.

When you help to restore a patch of degraded land through rewilding to forests, meadows, or wetlands, you have a massive impact on the biodiversity at a local level. You give animals a home and food that they otherwise would not have had, and it has a positive snowball effect for the food chain.

We are convinced that this is much better for the UK than growing lots of fast-growing coniferous trees, solely to remove carbon, that don’t actually help our animals to thrive.

This is why we stand for restoring nature in the UK through responsible rewilding. For us, it is the right thing to do. Let’s do what’s right for nature!

Donate today at https://naturalworldfund.com/ and join in the solution!