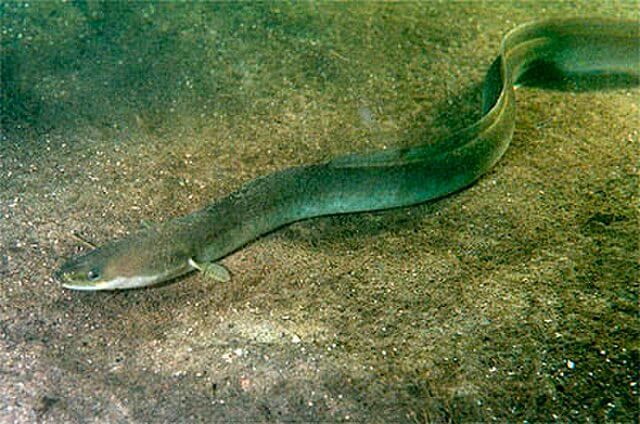

Eel experts have been left astounded by the conspicuous absence of these critically endangered creatures in the intricate network of drainage ditches that constitute their traditional habitat in the Somerset Levels.

Once, these marshlands were bustling with eels, but recent DNA sampling by the Sustainable Eel Group and Somerset Eel Recovery Project yielded no traces of eel DNA within the drainage ditches.

The Somerset Levels, an expanse of flat landscape spanning northern and central Somerset, encompasses around 69,000 hectares (170,000 acres) of wetlands and coastal plains. This region, which was once untamed marshland, has been subjected to human drainage and farming practices dating back to ancient times—evidence of drainage in the Levels predates even the writing of the Domesday Book.

Historically, it was a thriving haven for eels. Anglers seeking bream and roach in the area affectionately referred to small eels as “bootlaces” due to their propensity for entangling fishing lines. In fact, eels were so abundant that they even served as a form of currency in Somerset, with tenants of Glastonbury Abbey required to pay the monks an annual rent of 14,000 eels during the 12th century.

The prevailing theory among experts is that the extensive barriers constructed to safeguard farmland and residences by preventing water ingress are to blame for the absence of eels in the Levels’ drainage systems.

To investigate this puzzling phenomenon, eel advocates collaborated with the DNA sampling company NatureMetrics. They collected water samples, filtered them, and analysed the fragments for eel DNA.

Andrew Kerr, chair of the Sustainable Eel Group, said: “We were very, very surprised to see no evidence of European eel. Off the River Axe, there is an incredible network of drains built by man to drain the Somerset Levels. And we thought we would find eels throughout the whole area.

“Something like 100 million eels a year come up the Bristol Channel, going into the Parrett and the Somerset Levels and then on up the Severn, all the way up to Wales. And just as there are 1.3m barriers to fish migration in the rivers of Europe, the Somerset Levels are full of barriers, but we thought all these drains that surround the area of Wedmore, one of the great Somerset Levels, would be full of eels.”

While they detected varying quantities of eels in the rivers feeding into the Levels, there was a conspicuous absence of eels within the labyrinthine drainage networks of the wetlands.

“In the drainage ditches, we found no eel DNA. The river simply isn’t feeding the eels into the Levels, because they cannot cross the barriers,” said Kerr.

He also blamed an electric pumping station for killing the eels: “The drainage system is separate from the river system and is separated by barriers and walls and a great big pumping station.

“That electric pumping station has been there for 50 years. But obviously there were eels behind those walls before it went in, and eels have a lifecycle of 10 to 20 years, it takes some time for the pumps to kill them all. And that’s obviously what happened. We were very shocked to find no eel in that latticework of drains, it is ideal habitat.”

The situation is further compounded by the presence of a large electric pumping station, which is seen as a contributing factor to the eels’ demise. The drainage system operates independently from the river system, separated by barriers and walls, and the pumping station plays a role in this separation.

While complete removal of all barriers and flooding the farmland is not on the agenda, experts are advocating for making the water network more eel-friendly through barrier solutions.

“Nobody would expect you to turn it into a wilderness because you’d lose all that productive farmland. But what we have to do is find solutions to the blocked migration pathways.”

Ali Morse, water policy manager for The Wildlife Trusts, told the Guardian: “The Somerset Levels have been a stronghold for eels for thousands of years, but illegal fishing and the loss of wetland habitat have contributed to catastrophic declines. It is estimated that populations have decreased by as much as 90% since the 1980s. Somerset Wildlife Trust and partners are working hard to give eels a future in the Levels, including through release programmes and targeted reedbed management. It is critical we create and restore wetlands to give eels and other wildlife that depend on this vital habitat a future.”

The Sustainable Eel Group, in collaboration with local residents, will undertake a project to create traditional ropes that can be draped over these barriers. The concept is to provide eels with a path to traverse these obstacles, enabling them to migrate and restore their presence in this once-thriving habitat.

Kerr said: “We are building a great deal of local interest in eel. And that’s what’s triggering all this because the locals want their eels back. We’ve managed to connect them to their history and their tradition. And they’ve obviously are aware of it and frustrated that so little has been done, given the scale of the problem.”

A spokesperson for the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs said: “While our latest data shows eel populations have been recorded in sections of the Somerset Levels, there has been a decline in European eel distribution and abundance around Europe and north Africa over the last 30 years, including in the UK.

“This is why we are taking forward a range of measures to protect and support eel populations, including removing barriers to upstream migration by improving eel pass design in our rivers and carrying out research on all life stages of the European eel to inform conservation measures.”

——————————————————————————

At Natural World Fund, we are passionate about stopping the decline in our wildlife.

The decline in our wildlife is shocking and frightening. Without much more support, many of the animals we know and love will continue in their decline towards extinction.

When you help to restore a patch of degraded land through rewilding to forests, meadows, or wetlands, you have a massive impact on the biodiversity at a local level. You give animals a home and food that they otherwise would not have had, and it has a positive snowball effect on the food chain.

We are convinced that this is much better for the UK than growing lots of fast-growing coniferous trees, solely to remove carbon, that don’t actually help our animals to thrive.

This is why we stand for restoring nature in the UK through responsible rewilding. For us, it is the right thing to do. Let’s do what’s right for nature!

Donate today at https://naturalworldfund.com/ and join in the solution!