The unprecedented marine heatwave of 2023 was consistent with climate model predictions, according to new research, as scientists warn that such extreme events are likely to become increasingly common.

The “unheard-of” heatwave off the UK and Irish coasts, which occurred during a summer of 40°C temperatures, raised alarm over the survival of fish, shellfish, and kelp populations.

During the event, sea temperatures in shallow waters around the UK – including the North Sea and Celtic Sea – soared to 2.9°C above the average for June and remained elevated for 16 consecutive days. This prolonged warming posed a severe threat to marine life.

A study conducted by the University of Exeter, the Met Office, and the Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (Cefas) found that despite the extraordinary nature of the 2023 event, there is now roughly a 10% chance of a marine heatwave of similar magnitude occurring each year.

Published in Communications Earth & Environment, the study used climate models to estimate the likelihood of heatwaves at or above the levels recorded in June 2023. In the Celtic Sea, off Ireland’s south coast, the annual probability of such a heatwave has risen from 3.8% in 1993 to 13.8% today. In the central North Sea, it has climbed from 0.7% to 9.8% over the same period.

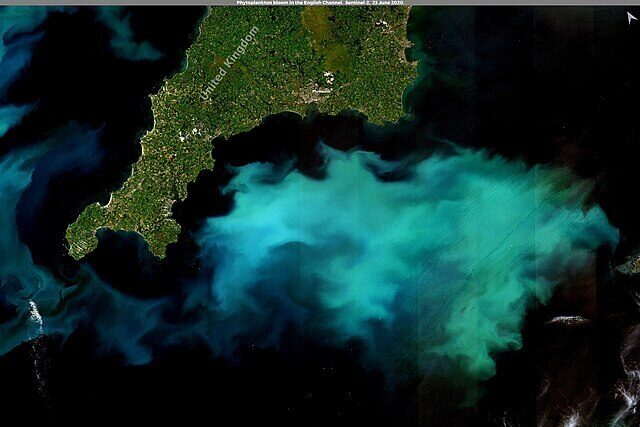

Although the full impact on marine ecosystems has yet to be determined, scientists report that the heatwave has significantly disrupted phytoplankton blooms. Marine heatwaves are known to stress sea life and can increase the presence of bacteria harmful to humans.

Dr Jamie Atkins, who led the study during his PhD at Exeter, and is now at Utrecht University, said: “Our findings show that marine heatwaves are a problem now – not just a risk from future climate change.”

Prof Adam Scaife, a co-author of the study from the University of Exeter and the head of long-range forecasting at the Met Office, said: “This is another example of how steady climate warming is leading to an exponential increase in the occurrence of extreme events.”

The extreme ocean temperatures also amplified heat on land across Britain and Ireland and contributed to episodes of heavy rainfall.

Atkins said: “Warmer seas provide a source of heat off the coast, contributing to higher temperatures on land.

“Additionally, warmer air carries more moisture – and when that cools it leads to increased rainfall.”

Prof Ana M Queirós at the Plymouth Marine Laboratory said: “Long marine heatwave periods push wildlife into a situation where seasonal ecological processes, such as reproduction, and even offspring hatching, are tricked into taking place at a time when other environmental conditions are not suitable.

“This is certainly a very bad sign for the health of our planet and our ocean, and one likely to worsen unless we make significant strides to cut emissions.”

——————————————————————————

At Natural World Fund, we are passionate about restoring habitats in the UK to halt the decline in our wildlife.