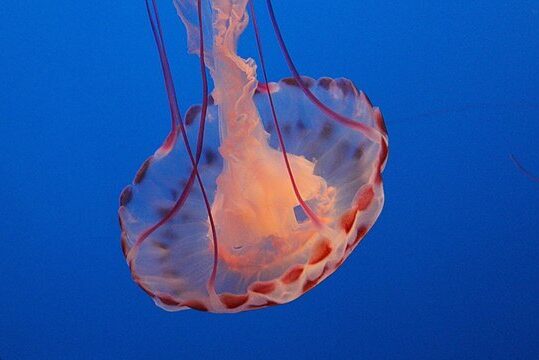

An experiment exploring the potential impacts of seabed mining on deep-sea life has unveiled unforeseen consequences, particularly affecting common jellyfish.

The burgeoning interest in extracting valuable minerals from metallic “nodules” on the seabed has raised concerns among marine scientists regarding potential harm to the delicate ecosystems below the ocean’s surface.

In an effort to understand the implications, researchers focused on helmet jellyfish, subjecting them to simulated mining conditions in specially designed tanks aboard a research vessel. The findings, published in Nature Communications, underscore the jellyfish’s high sensitivity to sediment plumes, shedding light on the possible ecological repercussions of deep-sea mining.

Seabed mining has been a contentious topic for decades, with proponents arguing for its environmentally friendlier approach to obtaining minerals compared to land-based mining. They contend that this method could address the growing demand for materials essential to green technologies.

However, opponents, including many marine scientists, caution that the consequences for marine life remain poorly understood, especially in the vast and largely unexplored depths of the ocean. The potential for irreparable damage to ecosystems, some of which may be undiscovered, has fuelled opposition to seabed mining.

The recent experiment, led by Dr. Helena Hauss from the Norwegian Research Centre NORCE, sought to address the dearth of research on the impact of mining activities on creatures navigating the water column—the expansive area between the ocean’s surface and the seabed.

“The idea was to get hold of an organism that’s globally distributed, and that would be exposed to these conditions in the real world,” she explained.

Due to the jellyfish’s sensitivity to light, the experiments were conducted during the night. Approximately 60 helmet jellyfish were captured and placed in temperature-controlled tanks within a dark lab on the research ship, replicating the conditions created by underwater vehicles extracting minerals from the seabed.

Marine scientist Vanessa Stenvers, from the Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research in Kiel, Germany, said “These are rotating tanks. Essentially re-creating a situation where sediment is disturbed and doesn’t settle – it’s circulating through the water.”

The results, part of the European iAtlantic project, uncovered unexpected effects on the jellyfish. When coated in sediment, the creatures produced excessive protective mucus—a costly energy expenditure normally allocated to feeding or movement. Samples from the jellyfish also displayed signs of acute stress, including the activation of genes associated with wound healing.

Helmet jellyfish, found in oceans worldwide at depths of several thousand meters, possess fragile and gelatinous bodies.

“That’s not true just for jellyfish, but for worms, molluscs and lots of other animals that live in the water column,” explained Ms Stenvers.

“You can afford to be fragile, because you’ll be safe in the in the mid water.”

In their transparent water environment, communication is largely facilitated through bioluminescence, which is effective in clear water conditions. Seabed mining activities, as explained by marine scientist Vanessa Stenvers from the Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research in Kiel, Germany, are likely to alter the conditions these animals have evolved in, emphasising the potential disruption to their habitats by mining-induced changes in sediment levels and water clarity.

——————————————————————————

At Natural World Fund, we are passionate about stopping the decline in our wildlife.

The decline in our wildlife is shocking and frightening. Without much more support, many of the animals we know and love will continue in their decline towards extinction.

When you help to restore a patch of degraded land through rewilding to forests, meadows, or wetlands, you have a massive impact on the biodiversity at a local level. You give animals a home and food that they otherwise would not have had, and it has a positive snowball effect on the food chain.

We are convinced that this is much better for the UK than growing lots of fast-growing coniferous trees, solely to remove carbon, that don’t actually help our animals to thrive.

This is why we stand for restoring nature in the UK through responsible rewilding. For us, it is the right thing to do. Let’s do what’s right for nature!

Donate today at https://naturalworldfund.com/ and join in the solution!