A recently published peer-reviewed study has raised doubts about the efficacy of PFAS-based products in repelling water and stains on fabrics used in furniture, shoes, clothing, carpeting, outdoor gear, and other consumer goods.

PFAS, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, are a class of approximately 14,000 chemicals known for their water, stain, and heat resistance properties. However, they are also referred to as “forever chemicals” because they do not break down naturally and have been linked to a range of serious health issues such as cancer, liver problems, thyroid disorders, birth defects, kidney disease, and decreased immunity.

The study, which did not disclose specific brands, compared the performance of furniture fabric treated with PFAS to untreated fabric. It concluded that factors such as fabric type, wear, and consumer stain management were more significant in determining the effectiveness of water and stain repellency than the presence of PFAS. The authors of the study characterised PFAS as providing “no practical benefit” in this regard.

“It was surprising to us that it was so clear, but the reason we did the study is because we had been talking with textile manufacturers who said PFAS don’t make much difference, but nobody had studied it scientifically,” said Carol Kwiatkowski, a co-author and senior science and policy associate with Green Science Policy Institute, the non-profit behind the study.

PFAS-treated fabrics can release particles that contaminate indoor air, attach to dust, or be absorbed through the skin, posing a particular risk to homes with young children. Stain-resistant apparel and products for babies and children are commonly treated with these chemicals. Additionally, PFAS-based products contribute significantly to PFAS pollution in public spaces like airports or schools where heavily treated carpeting is prevalent. While some products are treated with stain repellents during production, numerous brands also offer home sprays that expose consumers to these chemicals.

The study focused solely on furniture fabric, and further research would be required to determine the effectiveness of PFAS in clothing or other fabric applications. However, the authors believe that the findings are likely applicable to other fabrics as well. Each fabric sample in the study was stained with water-based coffee and oil-based salad dressing. The study revealed that the water repellency of PFAS-treated samples significantly decreased with moderate wear, indicating the need for frequent reapplication to maintain effectiveness. Furthermore, the study found no advantage in using PFAS when stains were water-based, as coffee stains were easily washed out without the need for PFAS.

While five out of six PFAS-treated samples showed minor improvements in stain repellency when exposed to oil-based dressing under ideal conditions (gentle stain application and quick cleaning), PFAS-treated fabric performed worse than untreated samples under “non-ideal conditions.”

“This means worn PFAS-finished fabrics must be maintained by frequent cleaning, similar to the need for cleaning unfinished fabrics,” the authors wrote.

The authors concluded that material characteristics such as fabric type, pattern, and colour were more influential in reducing stain visibility. Fabrics with complex patterns and structures, such as a cotton and nylon blend with a sophisticated pattern or a polyester fabric with a two-colour checkerboard pattern, performed better in stain reduction. Conversely, fabrics with simpler patterns and even tones exhibited more visible staining.

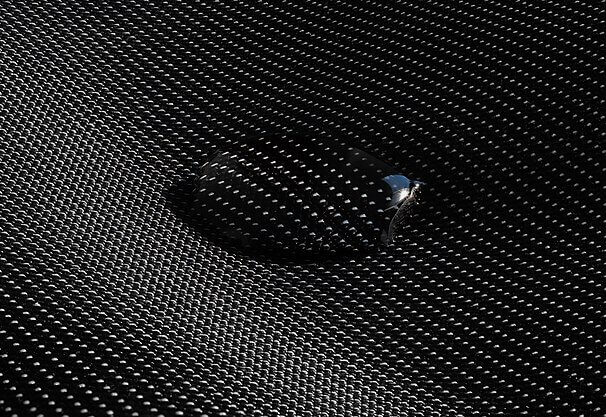

The construction of the fabric also played a role, as fabrics with looser woven structures, coarse yarns, and rough surfaces tended to trap liquid, keeping it invisible on the surface. On the other hand, fabrics with thinner fibres and denser weaves tended to keep staining liquids near the top of the fabric, making stains more visible.

Ultimately, the study suggests that the addition of toxic PFAS chemicals to furniture fabric is unnecessary.

“It makes you wonder what other uses of PFAS are also unnecessary and could be easily eliminated from products without noticeable change in performance,” said Jonas LaPier, a lead author on the study.

The American Chemical Council trade group responded to the study by requesting more time for review. Some repellent producers, including 3M, the manufacturer of Scotchgard, have announced plans to phase out the use of PFAS and have set a deadline in 2025 to stop manufacturing PFAS-based products.

It is crucial to minimise the use of PFAS-treated products as they ultimately end up in landfills, where the chemicals can contaminate the environment and drinking water through leachate or groundwater.

The EPA recently established low limits for some PFAS in drinking water, and no longer using the chemicals where they are not needed is essential to cleaning up widespread water pollution, Kwitakowski said.

“We should be stopping it on the front end,” she added. “We have to get to the point where we’re getting PFAS out of products, not just cleaning them up later.”

——————————————————————————

At Natural World Fund, we are passionate about stopping the decline in our wildlife.

The declines in our wildlife is shocking and frightening. Without much more support, many of the animals we know and love will continue in their declines towards extinction.

When you help to restore a patch of degraded land through rewilding to forests, meadows, or wetlands, you have a massive impact on the biodiversity at a local level. You give animals a home and food that they otherwise would not have had, and it has a positive snowball effect for the food chain.

We are convinced that this is much better for the UK than growing lots of fast-growing coniferous trees, solely to remove carbon, that don’t actually help our animals to thrive.

This is why we stand for restoring nature in the UK through responsible rewilding. For us, it is the right thing to do. Let’s do what’s right for nature!

Support our work today at https://naturalworldfund.com/ and join in the solution!